David Shor and the End of the "2016 Era"

Did "socialism" and "defund the police" hurt the Democrats in 2020?

I'm late to this, but David Shor’s latest interview for New York Magazine continues to fuel debate.

Shor, in case you haven't heard, is a numbers whiz for the Democratic Party whose data-driven takes on the party's electoral quandaries have won him something of a cult following in wonkland. You can check out his two previous interviews with New York's Eric Levitz (here and here), as well as the B̶l̶o̶g̶g̶i̶n̶g̶h̶e̶a̶d̶s̶ online dialogue he had recently with Bloomberg's Noah Smith on Smith's Substack. And you should: Shor always has interesting things to say.

The great leitmotif of the "Shor view" of American politics is educational polarization: the growing tendency over the past few decades for highly educated voters to vote Democrat and less educated voters to support Republicans. Shor sees this trend as particularly bedeviling to Democrats — for two reasons:

Geographically, the party's weakness among non-college educated whites puts it at a severe disadvantage, due to the highly "efficient" way those voters are distributed among different states and districts.

Culturally, Shor sees a vast disconnect between less-educated voters of all backgrounds (not just whites) and the highly educated political professionals who staff Democratic campaigns and party institutions — a mismatch that, he argues, seriously distorts the party's perceptions of how you win elections.

It's funny for me to see the warm reception accorded to Shor's ideas over the past year, because to me they harken back to the mini-Kulturkampf that so enlivened the Democratic primaries in 2016. Re-reading some of the things I wrote in Jacobin in the heady days of Bernie versus Hillary — arguments that were definitely not in keeping with prevailing center-left opinion at the time — I can't avoid the thought that some of them, in retrospect, sound positively Shor-esque.

For example, in a piece I wrote in the summer of 2015, I sparred with what was then a newly emerging liberal doxa: the idea that, in contrast to Hillary Clinton, who consciously embraced the rhetoric and symbolism of intersectionality, Sanders' brand of left-populism was "deaf" to the concerns of people of color, suffered from class-first "blind spots," and was otherwise riddled with identity-based handicaps so grievous as to elicit occasional mutterings about "Horseshoe Theory" and comparisons with Gregor Strasser (the German founder of the dirtbag left).

My take — which I illustrated with data from Gallup's venerable "Most Important Issue" question — was that this was a case of mostly white liberals projecting their own priorities onto working-class black and brown constituencies:

I’ll set aside the fact that the NAACP and the NHLA (the national Latino coalition) have both given Sanders 100 percent voting scores in every Congress of his Senate career — unlike Hillary Clinton.

Or that Sanders described the Ferguson police as resembling “an occupying army in a hostile territory” and voted against “declaring English the official language of the U.S. government, building a fence along the Mexican border, restricting immigrant visas for skilled workers and reporting undocumented aliens who receive hospital treatment.”

Or that Sanders spent the sixties in Chicago getting arrested as a SNCC organizer while a few miles away, in the suburbs, Hillary Clinton was doing her part as a “Goldwater Girl” with the Young Republicans at Maine East High School.

Sanders’s main offense, it seems, isn’t anything he’s failed to do or say. Rather, it’s his insistence on spending so much time talking about issues that are apparently irrelevant to the lives of black people or immigrants: jobs, wages, health care, college tuition, and the like. He drones on about poverty. He has never written a Beyoncé think-piece.

(It appears this piece struck a chord at the time with a little known data analyst named David Shor.)

In a similar vein, I recall often venting my irritation at a specific style of analysis found in so much liberal commentary in the "Era of 2016." We might call this the theory of political essentialism: the ubiquitous though seldom explicitly stated belief that mass political attitudes are simply the aggregates of millions of individual opinions, and that these opinions, being expressions of people' individual personalities, are for all practical purposes fixed and unchangeable — a function of demographics rather than anything that might be altered through properly political action. (It's an assumption that reaches its reductio ad nauseaum in the unpleasant political science literature sometimes referred to as "biopolitics" or "political physiology.")

I wrote about this just weeks before the 2016 election, in an article critical of the way liberals were then writing about the deplorable Trump Supporters. To make my point I pointed to the case of France:

Take the example of France, where the level of racism in political discourse seems to reach new heights every week and the far-right has been on the ascendant for decades. Yet the percentage of the French who say there are “too many immigrants in France” fell from 75 percent in 1988 to 50 percent in 2012. The percentage who think immigration is a “source of cultural enrichment” rose from 44 percent in 1992 to 75 percent in 2009. The percentage who agree that immigrant workers “should be seen as being at home here, since they contribute to the French economy” rose from 66 percent in 1992 to 84.5 percent in 2009.

In one sense, these figures — taken from a comprehensive 2013 study of long-run French public opinion by a team of political sociologists led by Vincent Tiberj of the Center for European Studies at Sciences-Po — shouldn’t come as a surprise. As the authors note, it’s long been understood that tolerance rises with education levels, and education levels have been rising for decades. Older and less-educated groups, in turn, are affected by the liberalizing cultural climate driven by younger and more-educated cohorts, albeit with a lag.

Thus, over the long run, each generation tends to express more tolerant attitudes than the last, and each generation tends to get more tolerant as it ages. “In all Western countries,” Tiberj says, “electorates are, generally speaking, more open and more tolerant than they’ve ever been.”

Yet you’d never guess any of that from watching the reactionary spiral of French political discourse. Tiberj explains the “paradox” this way:

Historically, France has never been more tolerant. Yet polarization on cultural values has never been as strong, either. The explanation is simple: If there’s a rightward shift, it’s above all a shift in the political debate.

When Mitterrand was reelected in 1988, the electorate still voted according to its socio-economic values. To put it simply, white-collar professionals voted for the right and workers voted for the left.

Starting with Nicolas Sarkozy’s [hard-right] 2007 campaign, things changed: voters started to vote according to both their socio-economic and their cultural values . . .

[And] while Nicolas Sarkozy didn’t hesitate to assert a right-wing ideological narrative to push a wedge into the debate, François Hollande has a lot more trouble with that . . .

Generally speaking, political discourse re-shapes the logic of voting: the rightward shift isn’t a demand coming from the electorate, it’s a result of the political supply . . . Our study tends to demonstrate the primordial importance of ideological combat.

Sensational events like riots, scandals, or terrorist attacks do cause short-run declines in tolerant attitudes, Tiberj finds. Eventually they’re forgotten and tolerant attitudes resume their long-run rise. But in the meantime, they can have long-run effects on politics by altering the terms of political debate — the ideological formulations offered by visible representatives of the Left and the Right. These are crucial in determining the tenor of the political discourse. And that tenor, in turn, alters how individuals understand their own relationship to politics, their own interests — even their own “motivations.”

“The same individual can simultaneously present dispositions to tolerance and to prejudice,” write Tiberj and his co-authors, “with the prevalence of the one over the other being strongly dependent on the environment, the information received, and recent events that have made an impression on them.”

If I'm taking you on this forced march down memory lane, it's only partly out of vanity. Mainly it's to emphasize the vast shift — of which the David Shor phenomenon is just one prominent sign — that has taken place in the Discourse since 2016. To put it simply, losing an election has a way of concentrating the mind. Whereas in 2016 arguments like the ones above were denounced as attempts to throw various oppressed groups "under the bus," the trauma of Trump's victory finally forced liberals to start thinking more seriously about how non-liberals approach politics.

Just a few years ago, for example, merely acknowledging the basic convergence of interests among different segments of the working class around a pro-labor, redistributionist program was condemned in some quarters as class reductionism. Today we see liberals broaching the suggestion that millions of Hispanic voters in 2020 readily set aside their racial and ethnic identities in exchange for a $1200 check from Donald Trump.

"Socialism" and "Defund the Police"

The astonishing Hispanic swing against the Democrats in 2020, which Shor estimates at 8-9 percentage points, was the focus of a good chunk of his recent interview in New York. In his view, two factors account for it.

The first is "defund the police," a meme that began its life as an activist slogan by police abolitionists during last summer's George Floyd protests, and quickly morphed into a Republican attack-ad line the following fall. According to Shor, the slogan had a major impact. "Clinton voters with conservative views on crime, policing, and public safety were far more likely to switch to Trump than voters with less conservative views on those issues," he tells Levitz. "And having conservative views on those issues was more predictive of switching from Clinton to Trump than having conservative views on any other issue-set was."

Shor also cites a second culprit: "the increased salience of socialism," as seen in "the rise of AOC and the prominence of anti-socialist messaging from the GOP." On this point, the evidence he cites is rather oblique, consisting entirely of the fact that some of the biggest Hispanic swings against the Democrats happened in places with a lot of voters from Colombia and Venezuela, two countries where, Shor notes, "socialism as a brand has a very specific, very high salience meaning."

In other words, Shor is saying that people who fled the ongoing disaster of the Maduro government in Venezuela or experienced the fallout of Colombia's war with the leftist FARC paramilitary got spooked by GOP rhetoric about "socialist" Democrats.

Action and Reaction

I'm going to come back to the specific question of Hispanic voting in a future Substack; here I want to look at how these two trends played out within the electorate as a whole, because the patterns Shor cites are of interest beyond just Hispanics.

The impact of the George Floyd protests on voting intentions turns out to be strikingly visible in the public opinion data. Here I'm going to draw on the monumental Nationscape survey, carried out by the Voter Study Group (a branch of the Democracy Fund). With more than 500,000 respondents surveyed in weekly interviews from July 2019 to December 2020, Nationscape is probably the biggest political poll ever fielded by a private-sector organization. I've been playing around with these numbers for more than a year now, and although the final batch (covering July-December 2020) hasn't yet been released, I'm continually amazed by the dataset's richness.

The numbers that have been released so far stop at the beginning of July 2020, four months before the election, so this analysis can't be conclusive. But it's remarkable to see how, just as the Floyd protests got underway in May 2020, respondents' answers to the Trump-Biden matchup question — "If the general election for president of the United States was a contest between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, who would you support?" — suddenly and sharply polarized around policing attitudes.

The chart below shows that pattern: respondents with the most favorable attitudes toward the police shifted sharply toward Trump, while those with the least favorable attitudes shifted sharply toward Biden:

The same dynamic is captured in a more comprehensive way in the chart below: it shows the correlation between respondents' attitudes toward the police, on the one hand, and their views of the two parties (or of Obama versus Trump) on the other.

From 2017 to mid-2020, this relationship was stable or getting weaker. But when the Floyd protests began, the correlation suddenly jumped to its highest level on the chart.

It's important to remember that nothing in the charts above can confirm for us whether the protests caused an overall increase or decrease in the Biden vote. What they do show is that the protests made the police issue dramatically more salient in voters' thinking about the election.

If we want to gauge the net electoral impact the protests might have had, we would need to examine at least two additional factors.

First, we would want to know the direct effect the protests had on attitudes toward the police — and here we can confidently say that effect was negative.

There's no question that, at least in the narrowest, short-term sense, the protests worked: they drew attention to an ongoing injustice and turned public opinion against it. The chart above shows the evolution of favorable and unfavorable attitudes toward the police before and after the unrest began.

This point deserves emphasis, because it's easy to forget that the four categories of police-favorability depicted in the topmost chart, above, do not represent timeless, unchanging groups of people; their memberships are constantly changing in size and composition.

As a result of the protests, two things were going on at the same time: (1) attitudes toward police were getting much more negative and (2) party voting intentions were getting much more polarized around police issues. Now, it might seem that that combination would militate in the Democrats' favor: if voters are souring on the police, and if they increasingly view the election through the prism of police issues, that should help the Democrats, right?

Not necessarily.

The problem is that, as the chart above shows quite clearly, the absolute share of favorable views of the police far exceeded the share of negative views, both before and after the protest-driven drop in support: the numbers were roughly 65% to 25% before the protests and 55% to 35% immediately afterward.

This gets to the nub of Shor's general argument: when the numbers on any issue are so lopsided, the math is unambiguous: the more electorally salient the police issue becomes, the worse it will be for Democrats even if public opinion on the issue is moving rapidly to the left. As long as there are far more people who like the police than dislike them, letting the topic dominate election-season discourse can reliably be expected to reduce the Democrats' vote share.

Actually, it's worse than that. Because if you look under the hood of the decline in support for the police, almost all of it was happening within the pool of Biden voters. In other words, the protests not only raised the salience of the police violence issue; they also made the issue more partisan. What happened, essentially, was that a significant number of Biden voters who had previously expressed friendly feelings for the police suddenly realized that this put them in the same camp as Trump supporters. In response, they duly changed their opinions about the cops.

I want to stress the critical importance of this type of dynamic. Here we have a case where a large number of people changed their attitudes about a pretty fundamental aspect of social life — like, "how do you feel about the people who are granted a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence in your community?" — in response to “feelings of friend and foe" arising from shifts in the configuration of party-political alliances — that is, based on politics.

The charts above don't prove that "defund the police" hurt the Democrats. They do, however, show that the protests had a major impact on the campaign: at least for a stretch of time, they recast the election in many people's minds as a referendum on law-and-order versus human rights, and they cemented those issues as Republican-versus-Democrat issues.

What about "Socialism"?

"Defund the police" and kindred topics burst into public discourse suddenly and at an easily identifiable moment in time: with the Floyd protests. That's why we can try to judge their effect on public opinion through an "event study" approach like the one above — by seeing how attitudes shifted right around May 2020, when the protests were exploding.

But "socialism" is different: there wasn't one big moment in 2020 when it came crashing into public consciousness; it was a constant, low-level, element of national political discourse that had been present since the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign.

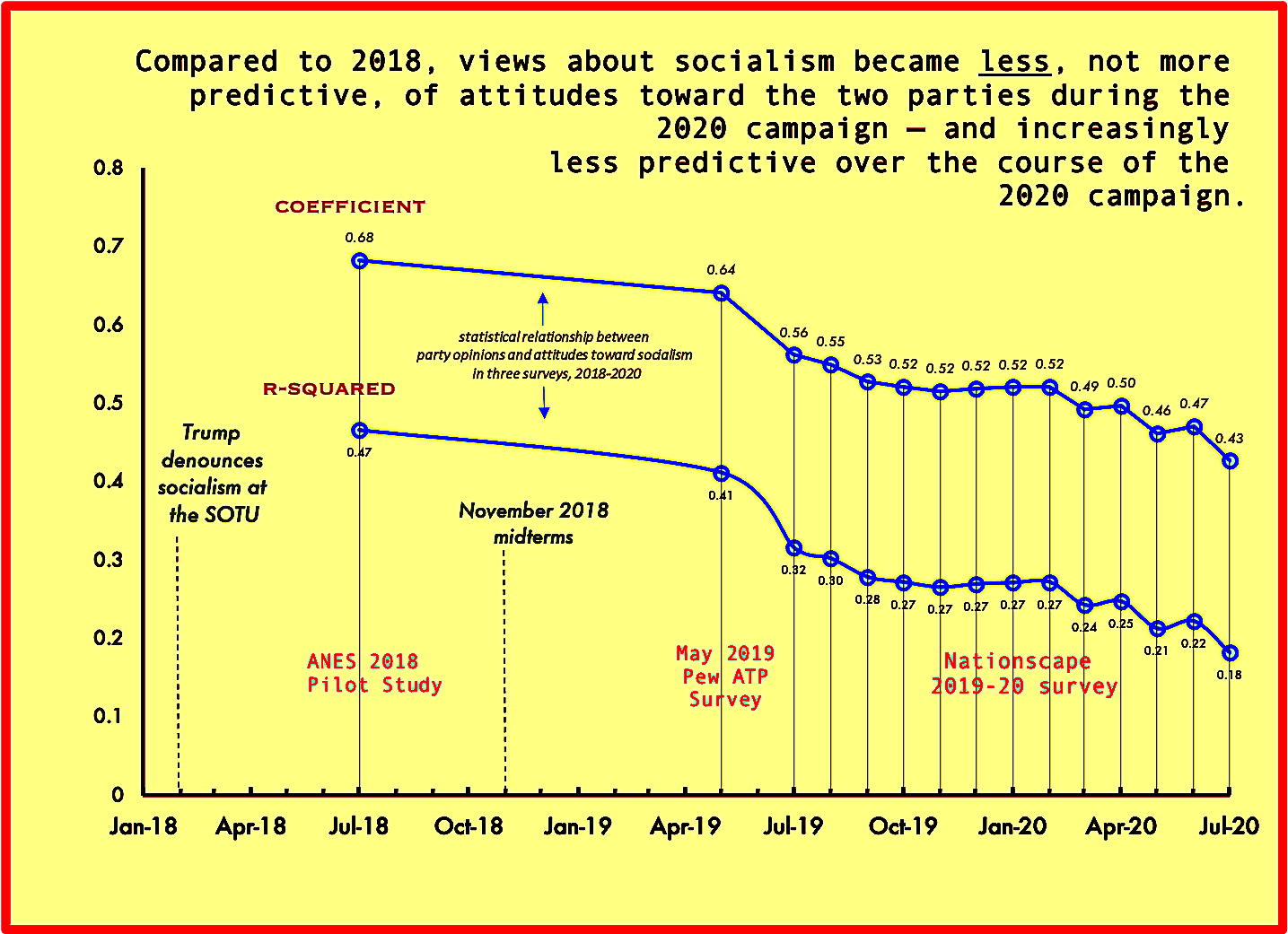

How then can we try to measure the effect of "socialism" in 2020? The best way, it seems to me, is to measure how strongly opinions of socialism predicted partisan attitudes in 2020 and compare that with the situation prevailing two years earlier, in the 2018 campaign.

Why 2018? Because, compared to both 2016 and 2020, that was a year of unquestioned Democratic success, as Shor points out. "In 2016, non-college-educated whites swung roughly 10 percent against the Democratic Party," he tells Levitz. "And then, in 2018, roughly 30 percent of those Obama-Trump voters ended up supporting Democrats down ballot. In 2020, only 10 percent of Obama-Trump voters came home for Biden."

It's not clear why voters should have been more worried about socialism in 2020 than in 2018, or why such worries should have hurt the Democrats more in 2020 than two years earlier. But if those things did in fact happen, they should have caused attitudes about socialism to become more tightly predictive of attitudes toward the Democrats.

Did that happen? No, it didn't.

The chart above shows the statistical relationship between favorable views of socialism and favorable views of the two parties (Democratic minus Republican) from three different surveys taken between mid-2018 and mid-2020. The upshot is clear: fears of socialism cannot plausibly be blamed for the 2018-to-2020 deterioration in the Democrats' electoral performance, because in 2020 opinions of the two parties were actually less correlated with attitudes about socialism than they had been in 2018.

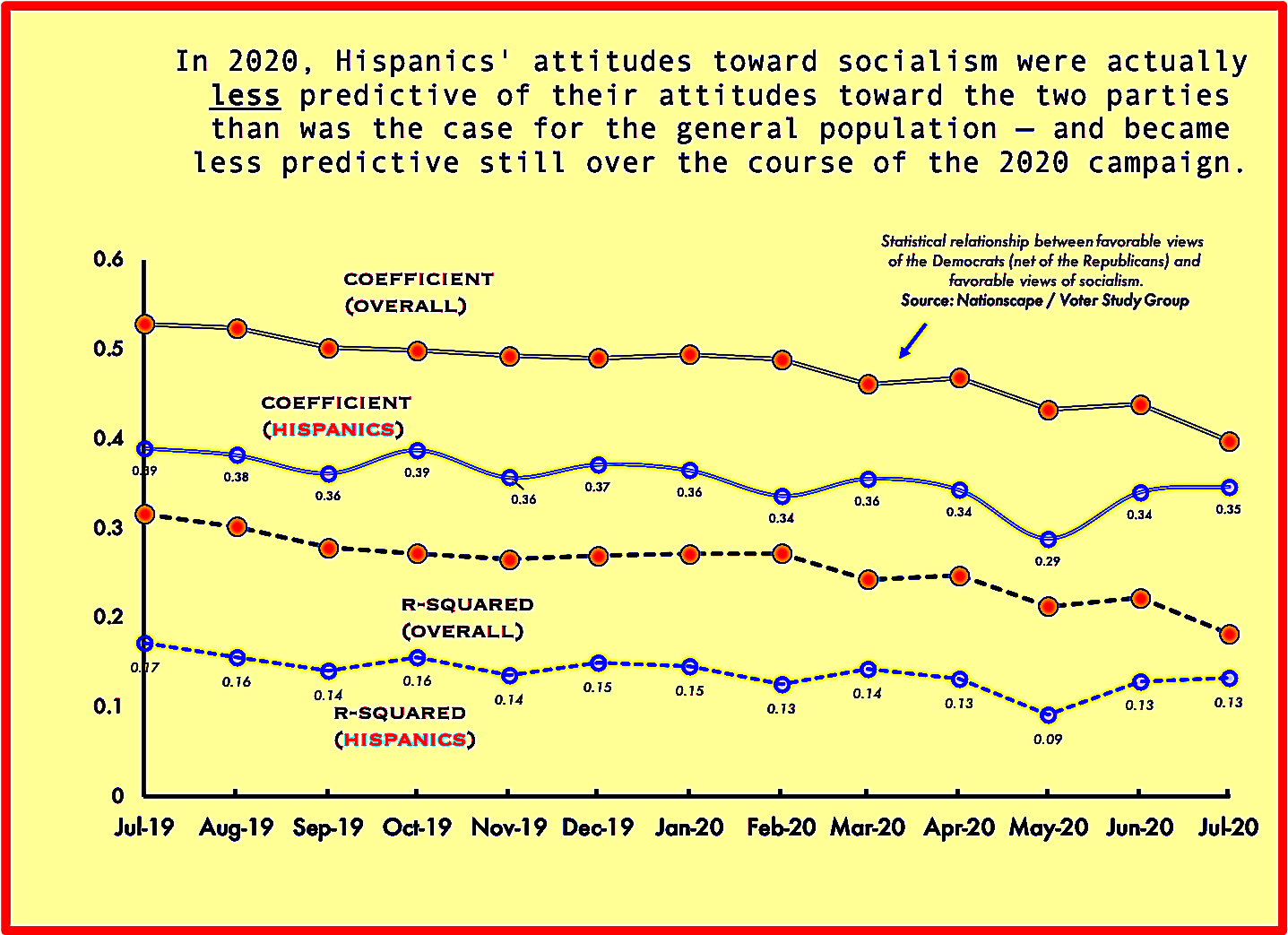

Nor does the socialism story seem to hold for Hispanics specifically, as Shor suggests. In fact, it turns out that among Hispanics, party-political attitudes are even less tightly tethered to views of socialism than is the case for the overall electorate.

Recall that the only data point Shor cites in support of his “socialism” thesis is the example of Colombians and Venezuelans, whose voting behavior, he says, evinced a sharp rightward lurch in 2020.

But even if we were to grant his inference that those shifts were driven by a fear of socialist Democrats, the fact is that Colombians and Venezuelans combined make up less than 3% of all Hispanics and just about one-half of one percent of the US population. Moreover — as I’ll discuss in more detail another time — Hispanics have consistently been the strongest supporters of Bernie Sanders of any race or ethic group, both in the 2020 Democratic primaries and in overall polling favorability.

Again, David Shor has a lot of insightful things to say about politics. But I think we can safely lay his “socialism theory” of the 2020 elections to rest.

I’ve been critical of David’s analysis in that it misses, most notably, the shifting salience of immigration as a factor in Hispanic vote choice. But I’ll defend his honor on the “socialism” point. It helps to disaggregate the national, baseline shift toward Trump among Hispanic voters, and the far accelerated shift we saw in South TX and South FL. Your data rightly identifies that fear of socialism isn’t predictive of the former (national shift). But it was undoubtedly a major factor in the massive Miami swing, which cost Dems two House seats.

Compared to the national shift— which happens after the midterms— in Miami it *began* during the midterm, among Cubans, stoked by AOC’s primary win and the nomination of Andrew Gillum for gov. In 2019, it extends to Venezuelans, and in 2020 to Colombians and others trapped in the Miami media ecosystem.

The result is that in Dem 2way support you see Clinton16 - NelsonGillum18 - Biden20 among Miami Cubans go 45-39-31, and among non-Cuban/non-PR Hispanics 70-60-52.

Even then, “socialism” is an oversimplification of a broader, multi-pronged attack. But it remains a useful shorthand.

We talked about the shift among younger, foreign-born Cuban voters here: https://equisresearch.medium.com/florida-deep-dive-on-the-cuban-vote-b5f66b0d9483

Very good write up and very clear for the depth of the analysis.

I have no disagreements with it as far as it goes, but let me suggest an additional factor beyond the topics and tenors of political and media discourse should be considered, especially the range of political activities approaching the 2020 election.

I refer to the regularly overlooked field program of Trump Victory in coordination with the RNC to 1) register new GOP voters and 2) to communicate more directly with a selected range of regional and ethnic groups.

This program was announced in late 2018 and launched in early 2019. It flew largely under the radar of national media, possibly through some combination of de-emphasis by the Trump campaign and disinterest from the general political press. But the campaign spent several hundreds of millions of dollars on these programs over the course of two years.

12/18/2018: https://www.politico.com/story/2018/12/18/trump-machine-swallows-rnc-1067875

5/8/2019: https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-campaign-hires-nine-regional-directors-for-2020-election-11557355628

1/17/2020: https://www.amny.com/politics/trump-campaign-tries-robust-outreach-to-expand-his-appeal/

01/23/2020: https://www.politico.com/news/2020/01/23/republican-nationa-committee-trump-battleground-102937

There was a Latinos For Trump website, established in June 2019, whose content was updated regularly : https://latinos.donaldjtrump.com/

For contrast (in the order of effort and tone) the Biden campaign website had an issue page for Latino Community: https://joebiden.com/todos-con-biden-policy/

My general point is that Trump Victory and the RNC made specific and sustained efforts and expenditures to reach out to a variety of ethnic communities traditionally seen as well beyond their base. Hispanic/Latino voters being the largest of these groups, any impact from this kind of outreach would be most visible there. It would be remarkable of such field-level programs had no impact at all, especially when Democratic energy during this two year period were at first taken up by their primary process (the GOP didn't undertake any significant primary promotional program), and then hampered by concerns about COVID. Even during the final months of the Biden-Harris campaign, observers noted that Hispanic/Latino outreach did not seem to be a priority for the campaign.

A related theory is that some voter registration efforts of the Trump/GOP programs increased non-Hispanic GOP registration in demographically high Hispanic counties, creating the illusion that more Hispanic voters flocked to Trump than actually did. A precinct-level analysis of new voter registrations, along with party-changing re-registrations, might shed some light, I've been hampered by technical problems and poor availability to pursue this inquiry, but it shouldn't be too hard to demonstrate or disprove with appropriate access to underlying data.

Anyway, thank you for the article.